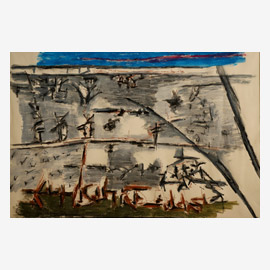

In the pluralistic and varied forms of art that existed in India in the course of the twentieth century it was notions of modernism which played a major role in bringing about transformations in consciousness. The opposition to academic art provided by the art colleges set up by the British in the 1850s was to lead to an art a century later which had a keen desire to break from its shackles and to carve an independent path which fore fronted individualism. Ironically, the post- colonial movements transformed the immobility, the mimetic and picturesque quality that existed into an art of great imaginative heights and power.

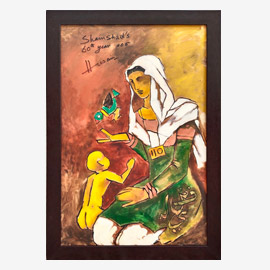

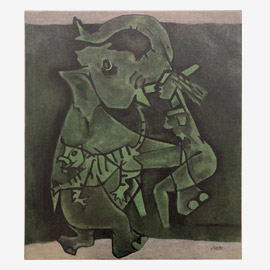

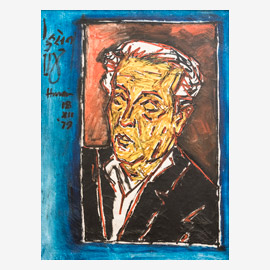

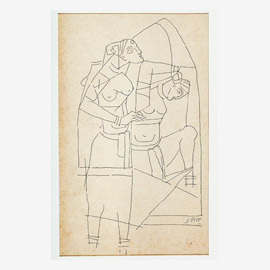

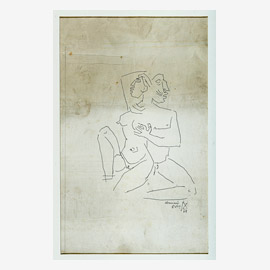

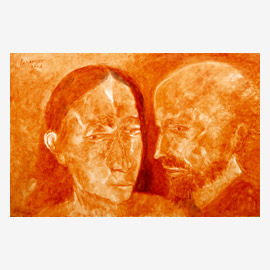

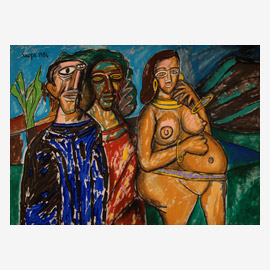

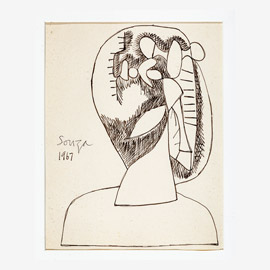

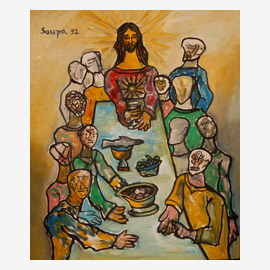

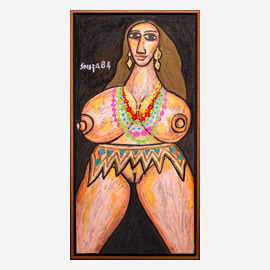

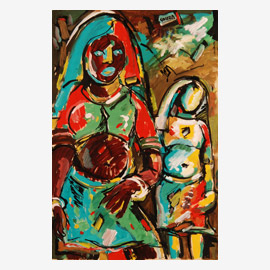

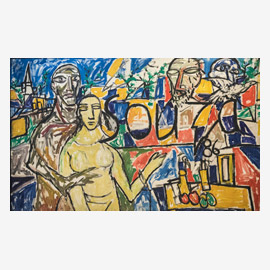

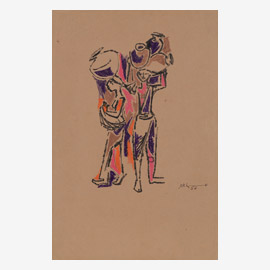

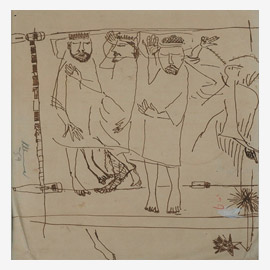

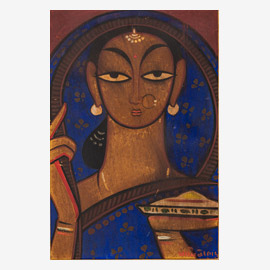

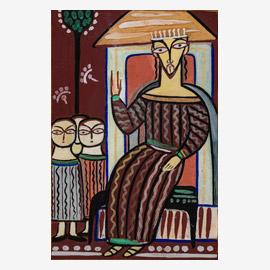

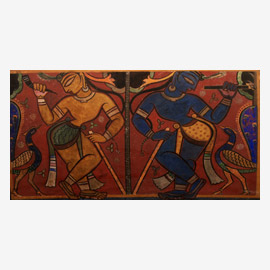

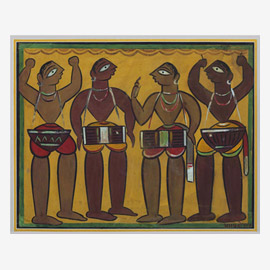

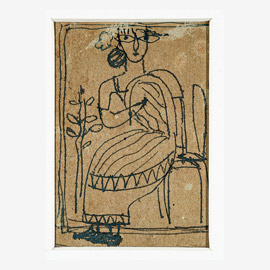

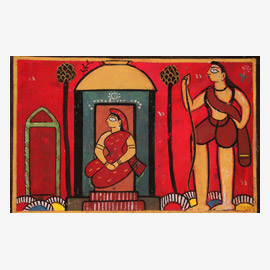

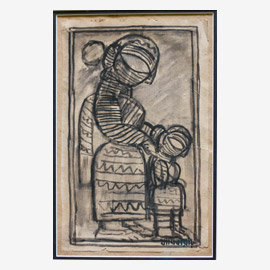

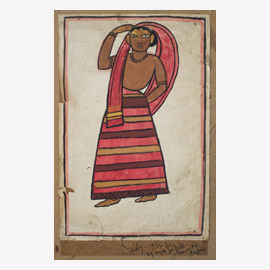

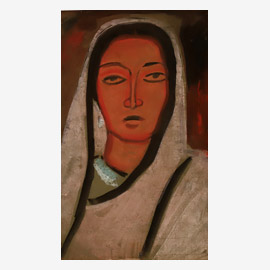

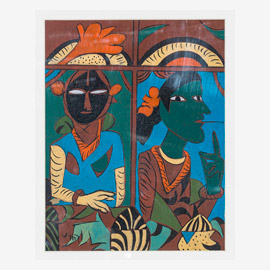

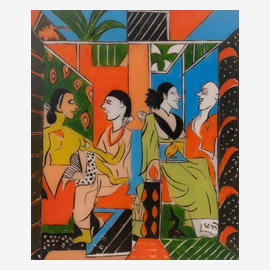

The dawn of modernism by mid-twentieth century was followed with artists overthrowing notions of academic art and creating a strong bid for the liberalizing of practices. Of these movements, the most vocal and forceful was the Progressive Artists’ Group, which was founded in 1947, coincidentally in the very year that India gained independence. The Group, consisting of F.N. Souza, M.F. Husain, S.H. Raza, K.H. Ara, S.K. Bakre and H.A. Gade, critiqued the outmoded practices of schools of art and rejected outright the revivalist approach of the Bengal School. While taking historical reality into account the artists found a means of assimilating it into the present. From the difficult terrain of Indian art where folk art[[forms]], the miniature schools, the Company school and an eclectic mixture of Western naturalism existed alongside, they were to create their own unique mode of expression. The Group, in its coming together, also symbolized the transcendence of the divisions created by religion, regions and caste.

The artists, were young and could barely eke out their existence but strove hard to achieve a language in art which would satisfy their need for expression as well as pave the way for modern Indian art in a nation striving for a selfhood. Relatively unknown at the time, some of them were to later become leading figures in art. Living as they did in congested spaces, they would travel long distances to meet downtown at the Bombay Art Society or by the sea at Marine Drive or at Rampart Row. As Raza recalls, ‘What we had in common besides our youth and lack of means was that we hoped for a better understanding of art. We had a sense of searching and we fought the material world. There was at our meetings and discussions a great fraternal feeling, certain warmth and a lively exchange of ideas. We criticized each other’s work as surely as we eulogized it. This was a period when there was no modern art in our country and a period of artistic confusion.’

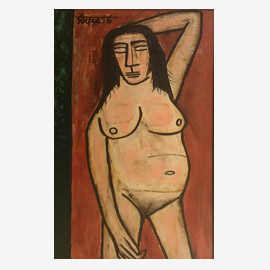

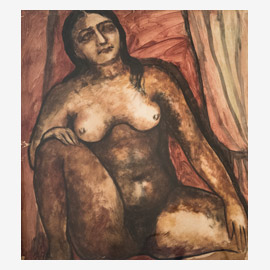

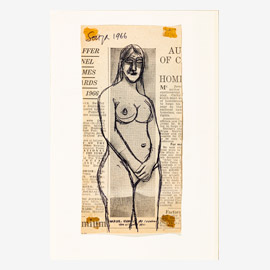

The artists met frequently, and held long discussions late into the night to find a means of expression in art which would reflect the needs of the country. As Raza defined it, ‘The real common denominator for us was significant form. We were expressing ourselves differently, we had different visions during the early days but what was common was a search for significant form, each in his own way, according to his vision. In a painted work, howsoever different it may be, say for example Modigliani and Soutine, who both painted nudes, the approach, the vision is different, the sensibility is different and, of course the temperament of these two artists is different. But the common denominator was significant form.’

The diverse forms of modernism which emerged in India were to signify the need for self-expression and set the path for the course of art in the following decades. In this multiple and textured modernism with its pluralistic influences there were conjectures of Indian art being imitative and hybrid. However, as Souza expostulated, ‘If modern art is hybrid, what is the School of Paris? Matisse is “Persian”, Van Gogh is “Japanese”, Picasso is “African”, Gaugin is “Polynesian”. Indian artists who borrow from the School of Paris are home from home’. A proliferating, multiple modernism set in by the sixties, as wide-ranging and heterogenous as the country itself, setting the ground for successive generations.

References

- S.H. Raza in ‘Point of Creation’ by Shirin Bahadurji, Bombay Magazine, 7—21 March 1984.

- S.H. Raza in an interview with the author, Mumbai, January 1991

- F. N. Souza, ‘Cultural Imperialism’, Patriot Magazine, February 12, 1984